In the case where n = 0, the left-hand side of (3) reduces to f(∅) and the right-hand side is the empty sum once again, because there are no subsets of ( is the set of the integers greater than or equal to 1 and less than or equal to 0, and there are of course no such integers). We shall use another inductive proof, within the inductive proof we’re currently carrying out, to show that Bonferroni’s inequalities hold for every in when m has this particular value. Now, suppose and Bonferroni’s inequalities hold in the case where m = M, and consider the case where m = M + 1. Which is true because f is non-negative- or ∞-valued. The only subset of of cardinality 0 is the empty one, so in this case the sum on the right-hand side of (3) is empty and (3) therefore reduces to the statement that In order to prove that Bonferroni’s inequalities hold, and thus prove the inclusion-exclusion principle, we can use induction. Because there are both even and odd integers m such that m ≥ n, and any quantity which is both less than or equal to and greater than or equal to another quantity has to be equal to it, it follows that Bonferroni’s inequalities imply that the equation (2) holds and thus generalize the inclusion-exclusion principle. When m ≥ n, the sum on the RHS of (3) is exactly the same as the sum on the RHs of (2). Note that Bonferroni’s inequalities hold when m ≥ n as well as when m < n.

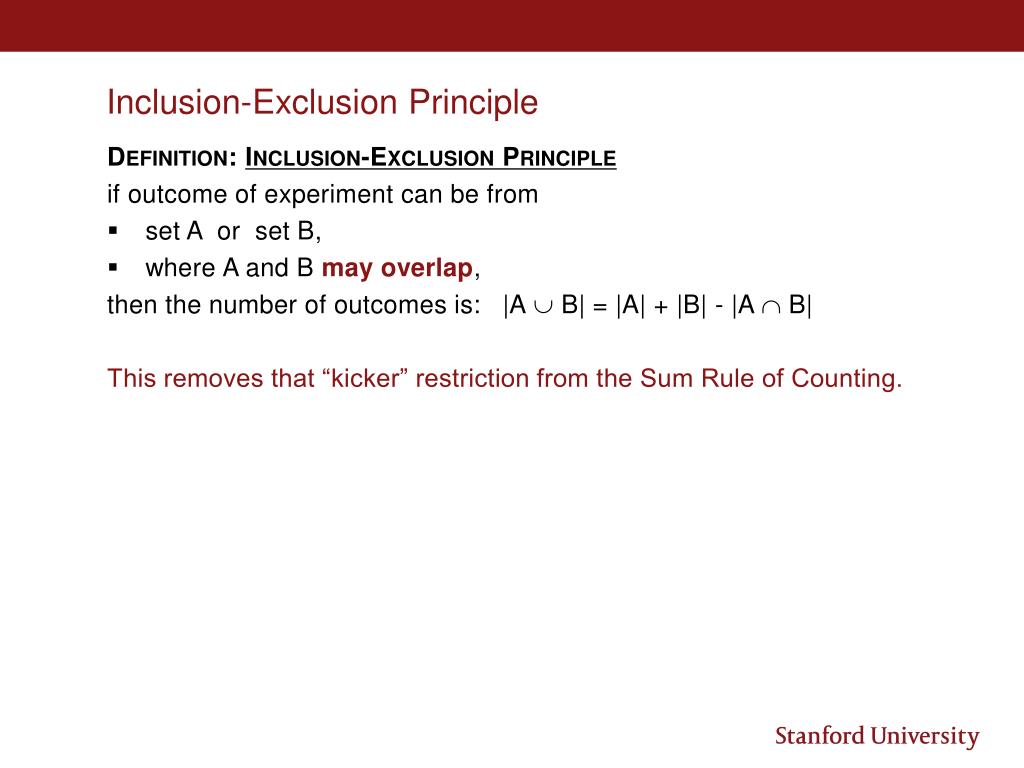

In particular, if m = 1 the terms are just the values under f of the individual sets A 1, A 2, … and A n and therefore we have The sum on the right-hand side of (3) has terms only for every non-empty subset of with no more than m members, and there are only 2 m − 1 of those. With the sign standing for “greater than or equal to, if m is even less than or equal to, if m is odd”.

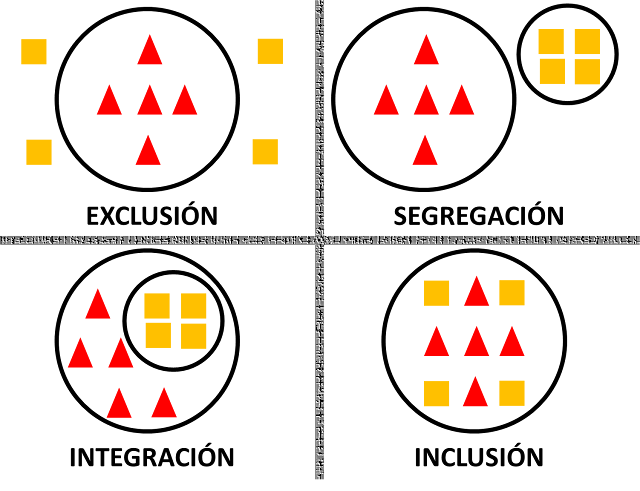

Therefore, it is also convenient to use Bonferroni’s inequalities, which say that for every, we have The sum on the right-hand side of (2) is a rather complicated one, cumbersome to write down as well as computationally expensive to compute by virtue of its large number of terms (one for every non-empty subset of, and there are 2 n − 1 of those). However, such unions’ values under f can be expressed in terms of the values under f of the individual sets and their intersections, by what is known as the inclusion-exclusion principle. Thenīut what about unions of sets in that are not necessarily pairwise disjoint? Can the values under f of such unions be expressed in terms of the values under f of the individual sets then? The answer is no. Now, suppose and (1) holds for every ( m + 1)-tuple ( A 1, A 2, …, A m + 1) of pairwise disjoint sets in. For every field of sets, every finitely additive mapping f on, every and every n-tuple ( A 1, A 2, …, A n) of pairwise disjoint sets in, we have In fact, the same can be said for unions of any arity, provided they are pairwise disjoint. The most important examples of finitely additive mappings are measures, including probability measures, although not every finitely additive mapping is a measure (measures are mappings on σ-algebras, which are a special sort of field of sets, that are countably additive, which is a stronger property than finite additivity).įrom the definition it is immediately evident that finite additivity allows us to express the value under a mapping f on a field of sets of any binary union of pairwise disjoint sets in in terms of the values under f of the individual sets. Send us feedback about these examples.A non-negative real- or ∞-valued mapping f on a field of sets is said to be finitely additive if and only if for every pair of disjoint sets A and B in, we have These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'exclusion principle.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Frank Wilczek, WSJ, That exclusion principle applies to the atoms in gas, too, which is what the scientists used to demonstrate it. 2022 Wolfgang Pauli’s exclusion principle, discovered in 1925 through studies of atomic spectra, showed the possibility of hole-like vacancies in atoms and molecules. Adam Becker, Scientific American, 22 Nov. 2012 Understanding the origin of Pauli’s exclusion principle would unlock explanations for all of these deep facts of quotidian life. Sean Carroll, Discover Magazine, 23 Feb. The Physics Arxiv Blog, Discover Magazine, Which also has nothing to do with the exclusion principle, so at least it’s consistent. The Physics Arxiv Blog, Discover Magazine, But these have a powerful negative charge that would overwhelm the subtle self-ordering effect of the exclusion principle. Recent Examples on the Web The exclusion principle ensures that electrons occupy different orbits around a nucleus.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)